As citizens, immigrants, and perhaps some First Nation people sit down across the country, give thanks over an overflowing centerpiece of abundance, and celebrate Thanksgiving for the harvest, we pause to consider one of the earliest attested parallels to our concept of the cornucopia from Ancient Egypt.

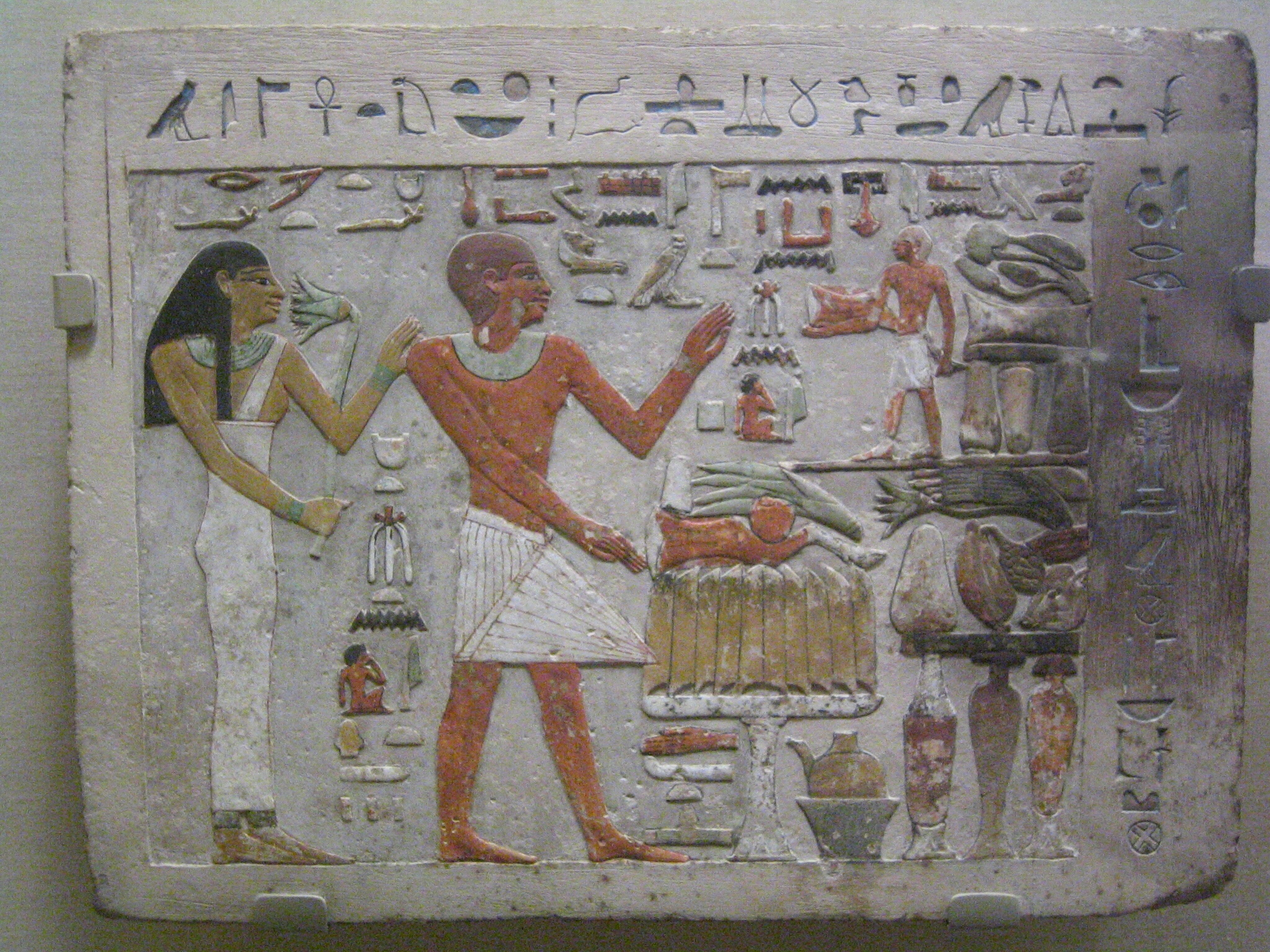

Placed upon the feast table in this Middle Kingdom wall fragment from the tomb of Amenemhet now in the Art Institute of Chicago, we see a tidy row of what appears to be sliced bread (yes, the Ancient Egyptians invented sliced bread) amidst a plethora of food and drink: ox leg, leeks, beer, wine, fowl…

Placed upon the feast table in this Middle Kingdom wall fragment from the tomb of Amenemhet now in the Art Institute of Chicago, we see a tidy row of what appears to be sliced bread (yes, the Ancient Egyptians invented sliced bread) amidst a plethora of food and drink: ox leg, leeks, beer, wine, fowl…

Notice, though, that the slices of bread taper at the tops to nifty little points and the bottoms are curved to taper similarly to single points engaging with the offering table. Unless we can also credit the Egyptians for inventing Italian panettone, I’m not sure that’s entirely expected of sliced bread.

What we have here is the beautiful interplay of word and image. A hybrid of Egyptian hieroglyphs and pictorial art. Sitting up on the table is not a representation of sliced bread, but the Egyptian hieroglyphs depicting a flowering reed. Phonetically it approximates our letter “I” or “J,” but in the context here at functions as an ideogram instead of a phonogram…that is, as an idea instead of a sound. The idea of the flowering reed is a veritable cornucopia of all the fruit of the fields placed upon the offering table of Amenemhet. It’s symbolic value will stand in place of the literal, physical food offerings placed at the tomb by Amenemhet’s descendants and contracted priests, nourishing the deceased in perpetuity forever after.

The Ancient Egyptian cornucopia.