Greeting weary travelers and welcome to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m Lucas Livingston, the Polo to your Marco on our thrilling journey of ancient adventure.

Imagine once-upon-a-time hundreds of years before the Internet superhighway, there was once a vast network connecting the distant lands of the Far East with cultures of the wine dark Mediterranean. From the comfort of familiar surroundings, people across the known world could enjoy global music and browse exotic imports at a networked bazaar … and all before the advent of electricity. We call this network the Silk Road. For all y’all under the age of 20, this Silk Road’s got nothing to do with that illicit online social forum. [1] No, my Silk Road’s got your Silk Road beat by over 2000 years! Stretching thousands of miles from China’s capital Changan in the Far East to the Mediterranean Sea in the west, spanning thousands of years from as far back as the 2nd century BC up to the 14th century, the Silk Road was a revolution in cultural exchange. [2] The term “Silk Road,” however, is really a misnomer. Silk was just one of the many commodities exchanged along this route. Some other popular goods included spices, tea, ceramics, other textiles, metals, and minerals like cobalt. The term “Silk Road” also reflects a strong western bias, since silk was the most precious good making its way from east to west. Had a term for the Silk Road been coined by a Chinese scholar rather than by a 19th century German historian, we might well call it the “Horse Road.” Horses were such a popular commodity exported to China from Central Asia throughout antiquity as possessions of prestige, sport, and warfare. That 19th century German historian, by the way, was Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen, who is largely overshadowed in modern history by his brash nephew, Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the WWI flying ace the Red Baron.

Returning to the blue mineral cobalt, that’s a perfect example of the beautiful network of exchanges happening through the Silk Road. Cobalts was mind in Persia and exported to China, where it was ground down and utilized in Chinese underglaze blue and white porcelain pottery of the Yuan and Ming dynasties. This Chinese pottery, in turn, was highly prized in the west, and so made its way on merchant caravans across the desert sands back to Persia. This beautiful exchange ultimately broke down when cobalt deposits were finally discovered in China and the Persians at last developed their own underglaze blue and white pottery technique, but the purist would say that it pales in comparison to Chinese examples.

Returning to terminology, the Silk Road is also a misnomer because there was no single road. No on ramp to the Silk Road, here. It was a vast network of interconnected mercantile and pilgrimage routes.

Yes, pilgrims traveled these routes as much as merchants. In fact, much as our Internet today conveys knowledge in addition to commodities like music and movies, the Silk Road can be credited as a vehicle for the transmission of ideas as much as if not more so than a pathway for exchanging physical goods.

Most significantly, one such idea that spread along the Silk Road is Buddhism. Buddhism originated in the foothills of the Himalayan mountains, perhaps around the 5th century BC, though recent discoveries might push that date back a century or so. [3] This new faith caught serious traction and spread rapidly across the plains of India and throughout the Himalayas, including Nepal and Tibet, where it blended with the native animistic faith called Bon. Now, that alone is a topic for another episode, but this is why Tibetan Buddhism is so very distinct today from many other forms of Buddhism in India, China, Korea, and Japan.

In the first couple centuries of the Common Era, Chinese Confucian and Doaist religious scholars traveled along these precarious trade routes across the Himalayas and into India to learn more about this mystical foreign faith called Buddhism. They returned with sutras or spiritual texts and Buddhist images, which helped establish and grow this fledgling faith beyond the Himalayas. There’s a jar in the Art Institute of Chicago, which beautifully exemplifies the earliest contact and understanding that China had with Buddhism. [4] It dates to the Western Jin dynasty of the 3rd century, when Buddhism was first beginning to make inroads into China. It’s a little bit funky visually. Rather busy. There’s a whole lot going on with this jar. The jar is a symbolic funerary urn called a “hunping.” No actual cremains were placed inside this urn, but it served as a palatial spiritual dwelling for the soul. Decorating the vessel is a myriad of miniature ceramic figurines. Nestled amid the many birds, monkeys, bears, dragons, people, and Chinese Daoist immortals, we see a cute, little image of Buddha just barely poking his head out. You know it’s Buddha, because he’s seated in a meditative posture and sports his characteristic topknot and halo. Ok, wait! Don’t send the hate mail. That is, “…his characteristic ushnisha and aureole.” After a few centuries, China became dominated by Buddhism, but it’s fascinating to see at this early stage how Buddha simply blends in with a medley of native Chinese faiths and figures.

Buddhism didn’t only appeal to hermit monks and nuns, but also caught traction with the itinerant merchant class as a faith denouncing the rigid social hierarchy of the caste system, untethered to ancient traditions, and spreading broadly across the networks of the Silk Road.

The cultural heyday of the Silk Road’s mercantile economy was China’s Tang Dynasty from 618-907. There was an unprecedented wealth of foreign goods and cultural influence making its way into China at this time. You might regard this as a golden age of cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism.

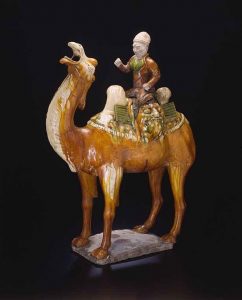

Suggestive of this cosmopolitanism is a marvelous assembly of ceramic tomb figurines in the Art Institute, which reconstructs the spectacle that the citizenry of 8th century China would have experienced as a merchant caravan traipsed into Changan off the dusty trails of the Silk Road. [5] Groomsmen lead horses and a Bactrian camel, while a rider deftly balances on the camel’s bouncing back. The rider pulls on now lost reigns as the camel rears its head, seeming to erupt in a gurgle characteristic of the breed’s cantankerous behavior. Looking closely at the faces of the human figures, with their heavy brows, sharp cheekbones, receding hairlines, and enlarged noses, the exaggerated expressions are on the verge of caricature and betray the distinctly non-Chinese features of central Asian merchants. Why? These ceramic figures were not made for just anybody. They cost quite a pretty penny and could only be afforded by nobility and the elite aristocracy. Why would an elite member of China’s upper class chose to decorate their tomb with representations of foreigners? It’s unclear why, but at the very least this is evocative of the rich multiculturalism rampant in the Tang dynasty, that a Chinese aristocrat would choose to be buried surrounded by foreigners.

Check out the marvelous glazing technique of these ceramic figures. This lovely multicolor drizzle and spatter effect is characteristic of the Tang Dynasty. It’s called “three-color” glazing or “sancai.” If you look close enough, you might find more than three colors, but it gets at the point that the artists were working with a limited palette for the lead-based glazing technique. Sancai is limited to the Tang Dynasty and profoundly stands out among the subdued glazing traditions throughout the rest of China’s history.

Another introduction to the artistic repertoire of the Tang Dynasty leads us to my favorite topic. You guessed it — alcohol. Okay, maybe not beer this time, but wine will serve as a close second. It’s during the Tang Dynasty that we see the introduction of grape wine to China and, when you know what to look for, you begin to see wine motifs springing up all over the place.

But we’ve run out of time, so we’ll just have to save that discussion for later. Be sure to tune in next time when we dig up the dirt on vines and wines in art at our roadside tavern along China’s Silk Road only on the Ancient Art Podcast.

——————-

Footnotes

[1] “Silk Road (marketplace),” wikipedia.

[3] James Morgan, “‘Earliest shrine’ uncovered at Buddha’s birthplace,” BBC News, 26 November 2013.

[5] Silk Road Caravan, Ancient Art Podcast’s online gallery at the Art Institute of Chicago.