Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, and critters of all nature, gather around. It’s time for the big numero uno in the series of the Top 10 Ancient Egyptian Myths and Misconceptions on the Ancient Art Podcast, episode 44: Egyptian Civilization is Dead!

The dynastic period of Ancient Egypt officially ended with the defeat and death of Cleopatra, but the civilization wasn’t suddenly destroyed or morphed into being Roman. For centuries to come, Egyptian culture, religion, art, architecture, and language continued to flourish under Roman occupation, and some of these facets of Egyptian civilization seep into Greco-Roman and Western Civilization, itself.

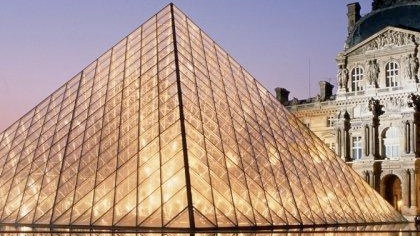

One of the most prominent architectural legacies from Ancient Egypt would be the pyramid. From the ancient Roman tomb of Gaius Cestius from 12 BC onward, the pyramids of Egypt have inspired countless funerary monuments. But is this indicative of a continuity of Egyptian civilization or just an homage to a bygone era? The pyramidal shape has been extended in modern times to structures entirely unrelated to their Ancient Egyptian funerary function, including I. M. Pei’s addition to the Louvre Museum, the 32-story, twenty-thousand seat Memphis arena, and that bastion of American values, Luxor Casino.

A little more subtle and perhaps more directly relevant to the discussion would be the influence of the Egyptian stele. Traditionally, a stele or stela is a slab of stone erected as a monument or documentation of an important event or decree. One of the most famous stelae is the Rosetta Stone, which was the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. Written in hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Greek, this decree from King Ptolemy V describes the repeal of various taxes and gives instructions to erect statues in temples, but that’s a rather late example from 196 BC. Stelae were used throughout Egyptian civilization. Another famous example is the Dream Stele of Thutmose IV from about 1,400 BC, which was erected by the king between the paws of the Great Sphinx. The text explains how prince Thutmose IV rested in the shadow of the sphinx when it spoke to him, revealing a divine message that he would be king if he cleared away the sands which had come to cover much of the statue. The stele was also very common as a funerary monument, as in this Middle Kingdom example from the Art Institute of Chicago. Here Amenemhet and his mother Yatu sit before the grave goods piled high on their offering table. Notice the rounded top both here and in the Dream Stele. Especially considering the stele’s funerary context, it’s probable that this is the prototype for the modern headstone.

Another type of artwork of similar shape and function is the mummy portrait. Its visual similarity to the stele is just coincidence. The mummy portrait wasn’t meant to stand upright in the ground, there’s generally no inscription, and the surface tends not to be as flat as a typical stele. Mummy portraits come from Egypt’s Roman era at a time when many well-off Roman individuals were residing in Egypt and a traditional Egyptian mummification became quite the fashionable way for these expatriates to go out in the end. So, a Roman-era mummy in Egypt would have a traditional anthropoid cartonnage body, like the Art Institute’s mummy of Paankhenamun from quite a few hundred years earlier, but it would be decorated with many Romanized pseudo-Egyptian funerary motifs. And instead of the wonderfully gilded face, they’d craft a blank area where the mummy portrait could slide into place. In contrast to the Egyptians, preserving the likeness of an individual after death was very important to the Romans. Often you’ll see that the mummy portrait is a bit convex in the forehead region, much like the rounded portion at the top, so it would nicely curve with the contours of the anthropoid mummy case.

While there could be a relationship between the stele, mummy portraits, and headstones, a far more probably direct connection would be between the mummy portrait and Orthodox Christian icons. The earliest form of organized Orthodox Christianity, the Coptic Church, was established in Egypt. Consecrated painted panels of venerated holy saints and other religious figures are widely used even to this day in the Orthodox community. The icon tradition can be said to go back to the time of Christ when my buddy, St. Luke the Evangelist, painted the very first icon portrait of Mary and Jesus. One simplified way to look at it would be that as Christianity waxed and the pagan religions waned, mummy portrait artists found their new niche as icon painters.

The subject of madonna and child wasn’t anything new either. Images of the goddess Isis holding the child god Horus became very popular in the Late Period of Egypt from the 7th century BC through the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. The cult of Isis spread throughout the Mediterranean in the Roman era and Isis shrines were often converted into shrines dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Similarly, early Christians adopted other pagan images and symbols of European and Mediterranean cultures, one perhaps being the divine mother and child so frequently portrayed in Coptic and other Orthodox Christian icons.

The word “coptic” can also be traced back to Ancient Egypt. It comes from the ancient Greek word for “Egypt,” Aigyptios. The English word “Egypt” also comes from the Greek. Aigyptios is thought to derive from the ancient Egyptian language, itself — from hwt-ka-ptah, meaning “the estate of the spirit of Ptah,” which was the Egyptian name for the temple of Ptah in Memphis. The Coptic language still survives today in liturgical practice and can be seen as the current evolutionary state of the ancient Egyptian language. It’s written with Greek letters plus a few extra Hieratic Egyptian signs that don’t exist in the Greek alphabet, but it’s linguistically closer to Egyptian. The Coptic word for an Egyptian person, for example, is rem en keme, which is just like the Egyptian phrase remet en kemet, meaning the “people of Egypt.” We can thank Coptic for our current best guess as to how the ancient Egyptian language may have sounded.

Besides the word “Egypt,” itself, there are a handful of English words derived from the ancient Egyptian language, sometimes indirectly via Greek, Latin, or Hebrew. The word “Pharaoh” comes from the Egyptian per-a’a, meaning the “Great House.” The name Susan comes from the Egyptian word for the lotus flower, seshen. Ebony and ivory come from the Egyptian words hebeny and abw, two precious commodities in Ancient Egypt. Ancient scholars valued Egypt as a cradle of wisdom and understanding. The great Library of Alexandria was the largest and most significant stronghold of scholarship in the ancient world, until Julius Caesar accidentally burned it down.

Our modern words “chemistry” and “alchemy” derived from the Arabic al-kimia (الكيمياء), coming from the Greek χημεία, which in turn likely derived from the Egyptian kemet. As we learned earlier, Kemet was the Egyptian word for Egypt, the “Black Land” of the rich, dark, alluvial silt from the Nile’s inundation. An alternative origin for al-kimia, though, could be from the Greek χυμεία, basically meaning “metallurgy,” but that word probably also derived from χημεία.

Other legacies of Ancient Egypt in the visual arts and architecture include the contraposto and colonnade. If you can remember way back in episode 15 on the “Origin of Greek Sculpture.” There we explored the direct relationship of the standing male Egyptian statuary form and the archaic Greek kouros. And we can see how this form evolves step-by-step into the familiar Classical and later Renaissance contraposto. And the colonnade, explored a little bit back in episode 5 on the Corinthian pixis — such a quintessential feature of Classical architecture, from the Parthenon to the Louvre and other modern centers of culture or government — it too has its roots in Ancient Egypt making its way westward by way of the Greeks during the Orientalizing period.

There are other connection between modern civilization and Ancient Egypt, which I won’t belabor you with, like the Horus > Harpocrates > Eros > Cupid connection or the dog-headed Saint Christopher as Anubis. I’ll let you research those on your own. But I do welcome your feedback if you know of any other slam-dunk vestiges of Egyptian civilization in our modern world. Now, with some apprehension, I feel it’s my scholarly duty to burst your bubble and dispel one more misconception. Despite whatever Pharaonic affiliations those squirmy critters may claim to have, the hairless Sphynx cat is in fact not an Ancient Egyptian breed.

We’ve come a long way with the Top 10 list and I hope you’ve enjoyed it. As I said at the beginning, this list isn’t exhaustive and isn’t necessarily in any order of priority, plus you may very well have some suggestions that ought to be included among the popular misconceptions about Ancient Egypt. I’d love to hear those suggestions. You can send me feedback at info@ancientartpodcast.org or online at http://feedback.ancientartpodcast.org. You can leave your comments on YouTube and iTunes, write your thoughts on the Facebook wall or send me a Tweet @lucaslivingston. If you follow the podcast on Facebook or follow me on Twitter, you may already know that I recently got back from a trip to Greece and Turkey with the Art Institute of Chicago. Out of the nearly 2,000 photos from my trip, I’ve whittled it down to the best few hundred, which you can check out online at http://resources.ancientartpodcast.org in the Resources section. Don’t forget to visit the rest of the website at ancientartpodcast.org where you’ll find the photo galleries and credits, links to other great resources, a bibliography, and remember there’s also the special page for the Top 10 list at http://www.ancientartpodcast.org/top10. Thanks for tuning in and see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2011 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Credits:

See the Photo Gallery for image credits.