Greetings, fellow swaggers, and welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. Previously in our pontifications on ancient indulgence, we explored the pivotal role of beer in Ancient Egypt as fuel for the pyramid builders, as an eternal offering to the gods and dead, as an excuse for inventing refrigeration, and as as an all-around-safer-to-drink-than-the-water beverage.

In this episode, let us turn away from the beverage of the unwashed masses to the finer drink, wine. As mentioned previously, wine in Ancient Egypt was something of a luxury commodity, a beverage for the elite. The earliest wine in Egypt from about 3,100 BC wasn’t even from Egypt. It was imported all the way from the Levant—what’s today around in the region of Jordan and southern Palestine. A massive cache of this imported wine was discovered in the tomb of King Scorpion I (yes, there really was a King Scorpion). This cache of wine would serve as sustenance for the king in the hereafter. While commoners like Amenemhet, whom we met last time, had to suffice with a mere reasonable number of physical offerings and a meager inscription promising a 1,000 vessels of alcohol, over 1,000 years earlier King Scorpion was buried with over 4,500 liters or about 1,200 gallons of the good stuff. It’s good to be the king.

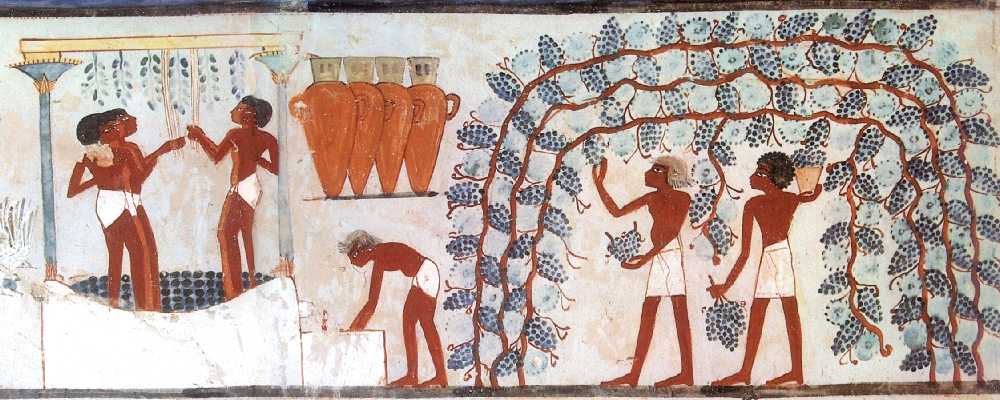

Wine didn’t take long to establish a foothold in Egypt. We soon see royal wineries cropping up and the institutionalization of wine in religious practice. [1] Egyptian wine included a variety of added ingredients like coriander, sage, thyme, mint, and other herbs and spices. They weren’t all added at once, but chemical analysis of ancient residue reveals different ingredients in different quantities. So you’d have a variety of styles and flavors. Fruit like figs and whole grapes or raisins were also added to enhanced the taste and possibly even help kick-start the fermentation. [2]

Wine was a contributing factor in the development of writing. With all those different varieties of wine, you’d want a way to keep track of your inventory. Some of the earliest hieroglyphs from Egypt are found on jar labels for food and wine. They were made from incised cylinder seals rolled over wet clay, a technique borrowed from the Ancient Near East. [3] Distinctions found on more elaborate wine labels included the names for the regions of origin, sometimes even including the estate and vintner name. Much as we today have recommended pairings of certain wine with fish, filet mignon, and duck, the Egyptians indicated their wine as being “wine for merry making,” “wine for offerings,” or “wine for taxes.” And in their reviews of wine, Ancient Egyptians pretty much cut to the chase with descriptions including “genuine,” “good,” “very good,” and “very very good.” [4]

Fast forward over 1,000 years past King Scorpion to the New Kingdom and we see a highly developed art of Egyptian wine-making and wine-drinking. On the magnificent painted wall fragments from the tomb of Nebamun now in the British Museum, we see a most sumptuous affair celebrating the deceased’s eternal feast in the afterlife. In one section, numerous elegantly dressed guests seated at a cocktail party are handed small drinking cups by young nude servants. The cups are likely meant to hold wine and we see the fruitful bounty of the funerary feast to the left, including meat, bread, fruit, notably ripe purple grapes overflowing their baskets, and numerous stoppered carafes of wine at their feet. Now, that’s a funeral I’d look forward to. And not that the Ancient Egyptians liked to immortalize anything unflattering, but elsewhere we even see the occasional good jab at these hoity-toity parties with graphic expressions of what these parties were really all about: overindulgence. And lest we still think the Egyptians thought too highly of themselves, the Egyptian word for wine was “yirp,” which some scholars today interpret as an onomatopoeic rendering of the sound one might issue after a little too much indulgence in the good stuff. [5]

Not much later than Nebamun, the young King Tut reigned over Egypt. In the manner of a king, Tut was buried with an abundance of grave goods of the highest quality. Among his many coffins, statues, jewelry, glowing lamps, and furniture was a magnificent Egyptian alabaster chalice, the so-called wishing cup. So-dubbed by King Tut’s discoverer, Howard Carter, this chalice prays that Tut’s ka (his soul) spend millions of years sitting toward the north wind with his eyes beholding happiness. It’s flowering lotus shape is flanked by two lotus handles surmounted by the god of eternity, Heh, grasping in each hand the hieroglyphic phrase for eternal life.

It’s conceivable that this magnificent work of art could have been crafted specifically as a funerary item, but my guess is that King Tut enjoyed this chalice so much in life that his beautiful young queen Ankhesenamun thought it only fitting that he continue to enjoy it in death.

Wine was consumed in Ancient Egypt with an almost religious proclivity. In fact, wine forms a central role in Egyptian mythology and religious rites. Looking back again to episode 51 on Beer in Ancient Egypt, we wrapped things up exploring the ancient legend of the bloodthirsty lion goddess Sekhmet, who was tricked into drinking a lake of beer dyed red with pomegranate, thinking it was the blood of her victims. Her severe intoxication thankfully curtailed the mass slaughter of humanity and transformed her into the gentler kitty-cat goddess Bastet.

This legend was very popular in Ancient Egypt and was reenacted annually in a sort of Spring Break Daytona Beach Girls Gone Wild Passion Play kind of thing. Our friend the Classical Greek traveler and historian Herodotus may have been witness to this festival, as he describes it with interesting detail in Book 2 of his Histories:

[This is the scene at Bubastis]: they come in barges, men and women together, a great number in each boat; on the way, some of the women keep up a continual clatter with castanets (κροταλίζουσι – “they shake rattles”) and some of the men play flutes, while the rest, both men and women, sing and clap their hands. Whenever they pass a town on the river bank, they bring the barge close [to] shore, some of the women continuing to act as I have said, while others shout abuse at the women of the place, or start dancing, or stand up and [hike] up their skirts. When they reach Bubastis, they celebrate the festival with elaborate sacrifices, and more wine is consumed than during all the rest of the year. [6]

And the archaeological record might corroborate this too. A 2006 report by archaeologist Betsy Bryan on excavations at the temple to the goddess Mut [7] in the Luxor Temple complex unearths some interesting evidence, including imagery heavily laden with sexual innuendo, like women fixing their hair and making beds for, well, you know. You also see images of lettuce, which was apparently thought to be an aphrodisiac, and lovers sharing figs. [8] We also find reference to an apparent “porch of drunkenness” associated with Queen Hatshepsut, and to some mystical rite known as “traveling through the marshes,” which was most likely a euphemism for having sex (perhaps not entirely unlike “hiking the Appalachian Trail.”)

The Egyptian New Year’s festival, held during the first month of the year, just after the first flooding of the Nile, re-enacted the myth of Sekhmet with an all-out, slap-happy, drunken frat party. But this festival of drunkenness wasn’t all just fun and games. After the massive drinking had taken its toll, the slumbering revelers would be wakened by thunderous drumming. The goal wasn’t merely to get drunk, but to experience a state of godliness similar to that endured by the inebriated Sekhmet. This communal sacrifice of sobriety to the goddess would have her bestow blessings upon the community and preserve it from harm. [9] Right, and Akhenaten read Nefertahtahs for the articles.

Well, we certainly haven’t emptied the whole bottle in the discussion of wine in Ancient Egypt, but for now, we’re going to put a cork in it. You can look forward to a future episode, where we set sail northward for an exploration of the beverages of Bronze Age Greece.

Thanks for tuning in to the Ancient Art Podcast. Don’t forget, for more exciting learning, check out the footnotes and references at ancientartpodcast.org for this and other episodes. You’ll also unearth a treasure trove of detailed images, image credits, and links to other great online resources. And as I divulged last time, if you’re game for following along as I delve deeper into the magical realm of home brewing with an ancient twist, check out my brew blog at ancientartpodcast.org/brew. You can like the podcast at facebook.com/ancientartpodcast and follow me on Twitter @lucaslivingston. I love reading your comments on YouTube, iTunes, and Vimeo, and you can email me at info@ancientartpodcast.org or send me your feedback on the web at feedback.ancientartpodcast.org. As always, thanks for tuning in and see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2012 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[1] McGovern, Patrick E., Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture, Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 102.

[2] McGovern, Patrick, Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages, University of California Press, 2009, p. 166. See also Patrick McGovern, “Wine for Eternity,” Archaeology 51.4 (July/August 1998), 28-34.

[3] Uncorking the Past 166.

[4] Ancient Wine 123

[5] Ancient Wine 87

[6] Herodotus. The Histories: Book 2, section 60. Trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt. New York: Penguin Books, 1972, p. 152-3.

[7] Mut, Hathor, Bastet, and Sekhmet all tend to blur together in Egyptian religion by the time of the New Kingdom, the fancy word for that being “syncretism.”

———————————————————

See the Photo Gallery for detailed photo credits.

Credits:

Metropolitan Museum of Art

British Museum

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Johns Hopkins University

drhawass.com

patmcgovern, flickr.com

davidrumsey.com

osirisnet.net

smithsonianmag.com

dailymail.co.uk

touregypt.net

grisel.net

wallcoo.net

deshow.net

historyforkids.org

fineartamerica.com

Greg Reeder, egyptology.com

caculo, The Freesound Project <freesound.org>

Wikimedia Commons

Apple