Hello and welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m your host, Lucas Livingston. In this episode, we’ll scratch the surface of one of the most interesting periods from Ancient Egypt, the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Any enthusiast of Ancient Egyptian history will probably have heard of Akhenaten, the so-called “Heretic King,” and if not Akhenaten, then at least you’ve heard of his wife Nefertiti, arguably the most famous Ancient Egyptian woman, second only to Cleopatra. Akhenaten ruled in the 18th dynasty from about 1353 to 1336 BC. In that relatively short time of only 17 years, he radically transformed Egyptian state religion and developed an entirely new artistic iconography.

Hello and welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m your host, Lucas Livingston. In this episode, we’ll scratch the surface of one of the most interesting periods from Ancient Egypt, the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Any enthusiast of Ancient Egyptian history will probably have heard of Akhenaten, the so-called “Heretic King,” and if not Akhenaten, then at least you’ve heard of his wife Nefertiti, arguably the most famous Ancient Egyptian woman, second only to Cleopatra. Akhenaten ruled in the 18th dynasty from about 1353 to 1336 BC. In that relatively short time of only 17 years, he radically transformed Egyptian state religion and developed an entirely new artistic iconography.

At the beginning of his reign, Akhenaten, who then went by the name Amunhotep IV, commissioned works of the traditional sort. As with many of his predecessors and successors, he built additions to the Temple of Amun at Karnak decorated in the very traditional canonic Egyptian style. But then in his second or third year he changed his name from Amunhotep to Akhenaten, which means something like the “Spirit of Aten.” So, he stripped the god Amun from his name and replaced it with Aten, the solar deity represented as a disk rather than an anthropoid god. Aten wasn’t anything new. His father King Amunhotep III already celebrated the cult of Aten, majorly elevating its status, and Aten as the life-giving power of the sun goes back at least as far as the Middle Kingdom.

The changes Akhenaten made were to more than his name alone. He outlawed many of the major cults, especially the cult of Amun, closing their temples and pissing off a lot of priests. He enforced the worship of Aten, with himself (and sometimes Nefertiti) as the sole intermediary between Heaven and Earth. He built a vast new capital city called Akhetaten, meaning the “Horizon of Aten.” Now it’s mostly rubble and sand, because it was destroyed after Akhenaten’s reign, and much of the rubble was used as filler for later additions to Karnak, but it once held huge open air temple courts where offerings were given up to Aten on a daily basis. The open air architecture was very different from the tiny, dimly lit, secretive back rooms of Karnak, Luxor, and other traditional Egyptian temples where a few special high priests would gather and perform sacred rituals enshrouded in mystery and secrecy.

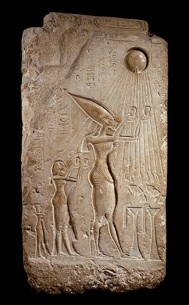

This is a fragment from the Great Palace at Akhetaten, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. On it we see Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their eldest daughter Meretaten praying and making offerings to the solar disk, much like we might imagine them having routinely done those many millennia ago. Notice the subtle linear band along the top of the scene. That’s actually the hieroglyphic character pet, meaning the “sky,” further reinforcing the doctrine of open-air worship to Aten. As the giver and sustainer of life, Aten’s rays of light reach down to its supplicants and hold symbols of the ankh, the hieroglyphic character for “life,” to their noses. In effect Akhenaten and Nefertiti breath in the life-granting essence of Aten. The hands at the end of Aten’s rays remain the only vestige of anthropomorphism to an otherwise abstract divinity.

This fragment exemplifies the innovative artistic style from the reign of Akhenaten, often called the Amarna style from Tel el Amarna, the modern Egyptian name for the area around what once was Akhetaten. The Amarna revolution abandons the idealized representation of the human form, especially the Pharaoh, who, as we might remember from our discussion of the statue of Ra-Horakhty back in episode 14, was always shown as an eternally youthful, muscular exemplar of human physique. The Amarna style, however, could be described as down-right caricature, a deformation of an individual’s characteristics. Just like the cult of Aten, itself, Akhenaten’s not uniquely responsible for inventing the Amarna style. He adopts, augments, and elevates many artistic characteristics that were already making their appearance during his father’s reign.

A couple other big developments in Egyptian art that the Amarna style picks up and runs with are the representation of movement and snapshots of moments in time. More typical of Ancient Egyptian religious and royal artwork is a very static timeless quality with almost no effort to represent any kind of action among the figures. But in the Amarna style, we definitely feel a sense of movement. Expression of emotion is also a big development that Akhenaten adopts from his predecessors. Take for example this delightful royal family portrait from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Here we see two young princesses cuddling up in the lap of Nefertiti, one daughter affectionately touching her mother’s chin. Akhenaten playfully dangles an earring like a piñata before Princess Meretaten. Note also the comfortable reclining pose that the king takes. I mean, this is a family at leisure, or at least they’re acting like it for the camera. All the while, the life-giving rays of the Aten shine upon them. This is all quite different from classic representations of the royal family like Menkaure with his wife here at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. A beautiful piece and sure she’s holding him with some minuscule degree of affection, but you have to wonder if they slept in the same bed. Of course, then the summer 2009 issue of Kmt, the popular journal on Ancient Egypt, has to go and accuse this lovely relief of Akhenaten and his family of being a modern counterfeit, but at least we still have this very similar example in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin. Check out the article “Nefertiti’s Final Secret” by Rolf Krauss in volume 20, number 2 of Kmt.

We also see a big change to the actual stylistic execution of relief carving. The sunken relief carving of the Amarna period is rendered with deeply cut, bold, smoothly flowing contour lines. Particular attention is given to detail, especially in individual parts of the body, like fingers and toes. Remember back at the end of episode 9, “Walk Like an Egyptian,” we learned that you never see little toes in Egyptian painting or relief carving. Well, the Amarna period may be the only general exception to this rule.

What makes the iconography of the Amarna style most distinctive, however, is the unusual physiology of Akhenaten and others. Instead of the ideal physical specimen of masculinity, Akhenaten is represented with an elongated face and head, full, heavy lips, enviably slender waist, spindly limbs, a pendulous belly, and thick, rounded thighs. … And Pharaoh got back! … So, what gives? It’s like Akhenaten’s trying to mix together exaggerated masculine and feminine characteristics. There’s absolutely no evidence to back up the idea that Akhenaten may have been physically deformed, although you come across a lot of people espousing that misconception. In fact, for many many centuries, the ancient god of the Nile’s annual flood, Hapi, was represented with breasts and a pregnant belly, yet masculine attire, a typical god’s beard, and otherwise generally masculine physique. Akhenaten is adopting an iconography similar to Hapi, blending masculinity and femininity into a singular being of idealized androgyny as the sole provider to the Egyptian people, thereby legitimizing his divine right to rule.

You get a lot of theories for why Akhenaten made the changes that he did to Egyptian society, religion, and art. Most of the theories are variants on the idea that he was either crazy or enlightened. He’s frequently given credit for introducing the concept of monotheism when all the rest of the world was running around worshiping different gods, rocks, and shrubbery, but that’s just not true. Akhenaten wasn’t a monotheist; he was more like a henotheist. Henotheism is the worship of one god, while believing that others exist and can get a little bit of credit too. Even though Akhenaten preached that the Aten was the one and only god, his motivation was largely political, not religious or ideological. In the generations leading up to Akhenaten, the state cult of Amun had risen to such unprecedented heights that it almost came to eclipse the authority of Pharaoh. The temple was the administrative and financial center of Egypt, holding massive tracts of land and immense influence over all aspects of Egyptian society and national affairs. In an effort not to become a puppet of the temple, Amunhotep III, Akhenaten’s father, already started to take measures to return to the unquestionable authority of Pharaoh, and Akhenaten took it that much further. But it didn’t work. Almost immediately after Akhenaten’s reign, Amun was reintroduced as the state god, royal iconography began reverting, and the Amarna style was dying out, giving rise to the Post-Amarna Period. But this fragment, rich in iconography, expression, and eternal supplication to Aten, is a prime example of the unique, short-lived, and beautiful artistic revolution of the “Heretic King” Akhenaten.

Want to learn more? Check out the bibliography in the Additional Resources section at ancientartpodcast.org. One particularly great resource is the catalog and website to the exhibition Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen from 1999. You can email me at info@ancientartpodcast.org. You can also give feedback on the website and fill out a fun little survey. And why not share the love with some iTunes comments? Thanks for listening and we’ll see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2009 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

]]>